England's

economy is one of the largest in the world, with an average GDP per capita of

£22,907.Usually regarded as a mixed market economy, it has adopted many free

market principles, yet maintains an advanced social welfare infrastructure. The

official currency in England is the pound sterling, whose ISO 4217 code is GBP.

Taxation in England is quite competitive when compared to much of the rest of

Europe—as of 2014 the basic rate of personal tax is 20% on taxable income up to

£31,865 above the personal tax-free allowance (normally £10,000), and 40% on

any additional earnings above that amount.The economy of England is the largest

part of the UK's economy, which has the 18th highest GDP PPP per capita in the

world. England is a leader in the chemical and pharmaceutical sectors and in

key technical industries, particularly aerospace, the arms industry, and the

manufacturing side of the software industry. London, home to the London Stock

Exchange, the United Kingdom's main stock exchange and the largest in Europe,

is England's financial centre—100 of Europe's 500 largest corporations are

based in London. London is the largest financial centre in Europe, and as of

2014 is the second largest in the world.

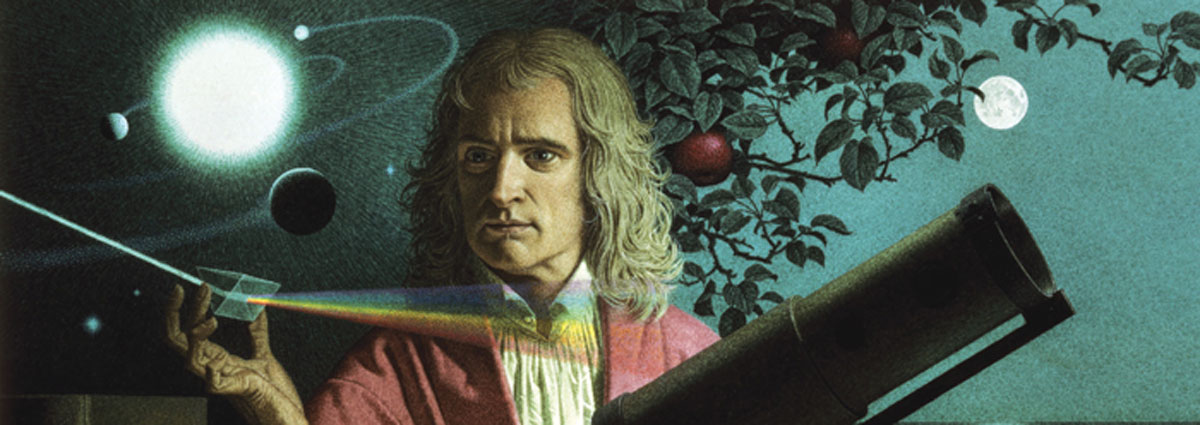

Prominent

English figures from the field of science and mathematics include Sir Isaac

Newton, Michael Faraday, Robert Hooke, Robert Boyle, Joseph Priestley, J. J.

Thomson, Charles Babbage, Charles Darwin, Stephen Hawking, Christopher Wren,

Alan Turing, Francis Crick, Joseph Lister, Tim Berners-Lee, Paul Dirac, Andrew

Wiles and Richard Dawkins. Some experts claim that the earliest concept of a

metric system was invented by John Wilkins, the first secretary of the Royal

Society, in 1668.As the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution,

England was

home to many significant inventors during the late 18th and early 19th

centuries. Famous English engineers include Isambard Kingdom Brunel, best known

for the creation of the Great Western Railway, a series of famous steamships,

and numerous important bridges, hence revolutionising public transport and

modern-day engineering. Thomas Newcomen's steam engine helped spawn the

Industrial Revolution. The Father of Railways, George Stephenson, built the

first public inter-city railway line in the world, the Liverpool and Manchester

Railway, which opened in 1830. With his role in the marketing and manufacturing

of the steam engine, and invention of modern coinage, Matthew Boulton (business

partner of James Watt) is regarded as one of the most influential entrepreneurs

in history.The physician Edward Jenner's smallpox vaccine is said to have

"saved more lives ... than were lost in all the wars of mankind since the

beginning of recorded history."

The

Department for Transport is the government body responsible for overseeing

transport in England. There are many motorways in England, and many other trunk

roads, such as the A1 Great North Road, which runs through eastern England from

London to Newcastle(much of this section is motorway) and onward to the

Scottish border.

The longest motorway in England is the M6, from Rugby through

the North West up to the Anglo-Scottish border.Other major routes include: the

M1 from London to Leeds, the M25 which encircles London, the M60 which

encircles Manchester, the M4 from London to South Wales, the M62 from Liverpool

via Manchester to East Yorkshire, and the M5 from Birmingham to Bristol and the

South West.

Bus

transport across the country is widespread; major companies include National

Express, Arriva and Go-Ahead Group. The red double-decker buses in London have

become a symbol of England. There is a rapid rail network in two English

cities: the London Underground; and the Tyne and Wear Metro in Newcastle,

Gateshead and Sunderland. There are several tram networks, such as the

Blackpool tramway, Manchester Metrolink, Sheffield Supertram and Midland Metro,

and the Tramlink system centred on Croydon in South London.

The

National Health Service (NHS) is the publicly funded healthcare system in

England responsible for providing the majority of healthcare in the country.

The NHS began on 5 July 1948, putting into effect the provisions of the

National Health Service Act 1946. It was based on the findings of the Beveridge

Report, prepared by economist and social reformer William Beveridge. The NHS is

largely funded from general taxation including National Insurance payments,and

it provides most of its services free at the point of use, although there are

charges for some people for eye tests, dental care, prescriptions and aspects

of personal care.

With over

53 million inhabitants, England is by far the most populous country of the

United Kingdom, accounting for 84% of the combined total.England taken as a

unit and measured against international states has the fourth largest population

in the European Union and would be the 25th largest country by population in

the world. With a density of 407 people per square kilometre, it would be the

second most densely populated country in the European Union after Malta.The English

people are a British people. Some genetic evidence suggests that 75–95% descend

in the paternal line from prehistoric settlers who originally came from the

Iberian Peninsula, as well as a 5% contribution from Angles and Saxons, and a

significant Scandinavian (Viking) element.However, other geneticists place the

Germanic estimate up to half. Over time, various cultures have been influential:

Prehistoric, Brythonic, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Viking(North Germanic), Gaelic

cultures, as well as a large influence from Normans. There is an English

diaspora in former parts of the British Empire; especially the United States,

Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand. Since the late 1990s, many

English people have migrated to Spain.

As its name

suggests, the English language, today spoken by hundreds of millions of people

around the world, originated as the language of England, where it remains the

principal tongue today. It is an Indo-European language in the Anglo-Frisian

branch of the Germanic family. After the Norman conquest, the Old English

language was displaced and confined to the lower social classes as Norman

French and Latin were used by the aristocracy.

English

language learning and teaching is an important economic activity, and includes

language schooling, tourism spending, and publishing. There is no legislation

mandating an official language for England, but English is the only language

used for official business. Despite the country's relatively small size, there

are many distinct regional accents, and individuals with particularly strong

accents may not be easily understood everywhere in the country.

According

to the 2011 census, 59.4% of the population is Christian, 24.7% non-religious,

5% is Muslim while 3.7% of the population belongs to other religions and 7.2

did not give an answer. Christianity is the most widely practised religion in

England, as it has been since the Early Middle Ages, although it was first

introduced much earlier, in Gaelic and Roman times. It continued through Early

Insular Christianity. The largest form practised in the present day is Anglicanism,

dating from the 16th-century Reformation period, with the 1536 split from Rome

over Henry VIII wanting to divorce Catherine of Aragon, and the need for the

Bible in the English tongue. The religion regards itself as both Catholic and

Reformed.

The culture

of England is defined by the idiosyncratic cultural norms of England and the

English people. Owing to England's influential position within the United

Kingdom it can sometimes be difficult to differentiate English culture from the

culture of the United Kingdom as a whole.

English

architecture begins with the architecture of the Anglo-Saxons. At least fifty

surviving English churches are of Anglo-Saxon origin, although in some cases

the Anglo-Saxon part is small and much-altered. All except one timber church

are built of stone or brick, and in some cases show evidence of reused Roman

work. The architectural character of Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical buildings

ranges from Coptic-influenced architecture in the early period, through Early

Christian basilica influenced architecture, to (in the later Anglo-Saxon

period) an architecture characterized by pilaster-strips, blank arcading,

baluster shafts and triangular-headed openings. Almost no secular work remains

above ground.

The food of England has historically been

characterised by its simplicity of approach, honesty of flavour, and a reliance

on the high quality of natural produce. This has resulted in a traditional

cuisine which tended to veer from strong flavours, such as garlic, and an

avoidance of complex sauces which were commonly associated with Catholic Continental

political affiliations. Traditional meals have ancient origins, such as bread

and cheese, roasted and stewed meats, meat and game pies, and freshwater and

saltwater fish. The 14th-century English cookbook, the Forme of Cury, contains

recipes for these, and dates from the royal court of Richard II. Modern English cuisine is difficult to

differentiate from British cuisine as a whole. However, there are some forms of

cuisine considered distinctively English. The Full English Breakfast is a

variant of the traditional British fried breakfast. The normal ingredients of a

traditional full English breakfast are bacon, eggs, fried or grilled tomatoes,

fried mushrooms, fried bread or toast, and sausage, usually served with a cup

of coffee or tea. Black pudding is added in some regions as well as fried

leftover mashed potatoes called potato cakes or hash browns.

English folklore is the folk tradition that

has evolved in England over the centuries. England abounds with folklore, in

all forms, from such obvious manifestations as semi-historical Robin Hood

tales, to contemporary urban myths and facets of cryptozoology such as the

Beast of Bodmin Moor. The famous Arthurian legends may not have originated in

England, but variants of these tales are associated with locations in England,

such as Glastonbury and Tintagel.

England has

a strong sporting heritage, and during the 19th century codified many sports

that are now played around the world. Sports originating in England include

association football, cricket, rugby union, rugby league, tennis, boxing,

badminton, squash, rounders, hockey, snooker, billiards, darts, table tennis,

bowls, netball, thoroughbred horseracing, greyhound racing and fox hunting. It

has helped the development of golf, sailing and Formula One.

Football is

the most popular of these sports. The England national football team, whose

home venue is Wembley Stadium, won the 1966 FIFA World Cup against the West

Germany national football team where they won 4–2, with Geoff Hurst scoring a

hat-trick. That was the year the country hosted the competition.

The St

George's Cross has been the national flag of England since the 13th century.

Originally the flag was used by the maritime Republic of Genoa. The English

monarch paid a tribute to the Doge of Genoa from 1190 onwards, so that English

ships could fly the flag as a means of protection when entering the

Mediterranean. A red cross was a symbol for many Crusaders in the 12th and 13th

centuries. It became associated with Saint George, along with countries and

cities, which claimed him as their patron saint and used his cross as a banner.

Since 1606 the St George's Cross has formed part of the design of the Union

Flag, a Pan-British flag designed by King James I.

There are

numerous other symbols and symbolic artefacts, both official and unofficial,

including the Tudor rose, the nation's floral emblem, and the Three Lions

featured on the Royal Arms of England. The Tudor rose was adopted as a national

emblem of England around the time of the Wars of the Roses as a symbol of

peace. It is a syncretic symbol in that it merged the white rose of the

Yorkists and the red rose of the Lancastrians—cadet branches of the

Plantagenets who went to war over control of the nation. It is also known as

the Rose of England. The oak tree is a symbol of England, representing strength

and endurance. The Royal Oak symbol and Oak Apple Day commemorate the escape of

King Charles II from the grasp of the parliamentarians after his father's

execution: he hid in an oak tree to avoid detection before safely reaching

exile.

After three hard years for Carter, in 1907 Lord Carnarvon employed Carter to supervise Carnarvon's Egyptian excavations in the Valley of the Kings. The intention of Gaston Maspero, who introduced the two, was to ensure that Howard Carter imposed modern archaeological methods and systems of recording.

After three hard years for Carter, in 1907 Lord Carnarvon employed Carter to supervise Carnarvon's Egyptian excavations in the Valley of the Kings. The intention of Gaston Maspero, who introduced the two, was to ensure that Howard Carter imposed modern archaeological methods and systems of recording.

.jpg)