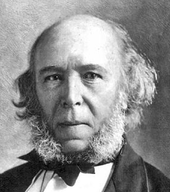

Born: 27 April 1820

Died: 8 December 1903

School: Evolutionism, Positivism, Classical liberalism

Notable ideas: Social Darwinism, Survival of the fittest

Was an English philosopher, biologist, anthropologist, sociologist, and prominent classical liberal political theorist of the Victorian era.

Spencer developed an all-embracing conception of evolution as the progressive development of the physical world, biological organisms, the human mind, and human culture and societies.

Spencer read with excitement the original positivist sociology of Auguste Comte. A philosopher of science, Comte had proposed a theory of sociocultural evolution that society progresses by a general law of three stages. Writing after various developments in biology, however, Spencer rejected what he regarded as the ideological aspects of Comte's positivism, attempting to reformulate social science in terms of evolutionary biology. One might broadly describe Spencer's sociology as socially Darwinistic (though strictly speaking he was a proponent of Lamarckism rather than Darwinism).

The evolutionary progression from simple, undifferentiated homogeneity to complex, differentiated heterogeneity was exemplified, Spencer argued, by the development of society. He developed a theory of two types of society, the militant and the industrial, which corresponded to this evolutionary progression. Militant society, structured around relationships of hierarchy and obedience, was simple and undifferentiated; industrial society, based on voluntary, contractually assumed social obligations, was complex and differentiated. Society, which Spencer conceptualised as a 'social organism' evolved from the simpler state to the more complex according to the universal law of evolution. Moreover, industrial society was the direct descendant of the ideal society developed in Social Statics, although Spencer now equivocated over whether the evolution of society would result in anarchism (as he had first believed) or whether it pointed to a continued role for the state, albeit one reduced to the minimal functions of the enforcement of contracts and external defence.

Though Spencer made some valuable contributions to early sociology, not least in his influence on structural functionalism, his attempt to introduce Lamarckian or Darwinian ideas into the realm of sociology was unsuccessful. It was considered by many, furthermore, to be actively dangerous. Hermeneuticians of the period, such as Wilhelm Dilthey, would pioneer the distinction between the natural sciences (Naturwissenschaften) and human sciences (Geisteswissenschaften). In the United States, the sociologist Lester Frank Ward, who would be elected as the first president of the American Sociological Association, launched a relentless attack on Spencer's theories of laissez-faire and political ethics. Although Ward admired much of Spencer's work he believed that Spencer's prior political biases had distorted his thought and had led him astray. In the 1890s, Émile Durkheim established formal academic sociology with a firm emphasis on practical social research. By the turn of the 20th century the first generation of German sociologists, most notably Max Weber, had presented methodological antipositivism. However, it should be noted that Spencer's theories of laissez-faire, survival-of-the-fittest and minimal human interference in the processes of natural law had an enduring and even increasing appeal in the social science fields of economics and political science, and one writer has recently made the case for Spencer's importance for a sociology that must learn to take energy in society seriously.

Social Darwinism

For many, the name of Herbert Spencer would be virtually synonymous with Social Darwinism, a social theory that applies the law of the survival of the fittest to society; humanitarian impulses had to be resisted as nothing should be allowed to interfere with nature's laws, including the social struggle for existence.Spencer's association with Social Darwinism might have its origin in a specific interpretation of his support for competition. Whereas in biology the competition of various organisms can result in the death of a species or organism, the kind of competition Spencer advocated is closer to the one used by economists, where competing individuals or firms improve the well being of the rest of society. Spencer viewed private charity positively so long as it did not encourage the procreation of the unworthy, as he believed in voluntary association and informal care as opposed to using government machinery.

Focusing on the form as well as the content of Spencer's "Synthetic Philosophy", it has recently been identified as the paradigmatic case of "Social Darwinism", understood as a politically motivated metaphysic very different in both form and motivation from Darwinist science.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario